Retractions: Righting the wrongs of science

If the results from an experiment look too right to be true, look over again.

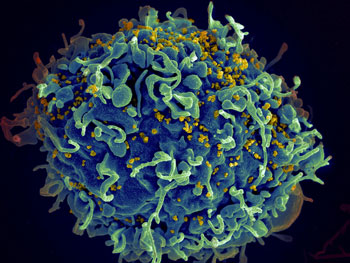

Those are advisable words to remember. Consider, for example, a recent case of what looked like a find in treating the lifelessly virus HIV. The findings sour out to be bogus. All it took was a second look.

A study reporting success with the vaccinum was published — and so later retracted. When a journal retracts a newspaper publisher, the study is removed from the organic structure of scientific evidence. IT means the study is and then flawed that it never should have been published in the first place.

Retractions can plurality a nasty sting for the scientists whose work was affected. But those retractions also play a necessary role. Acknowledging mistakes helps scientific discipline move forward.

Explainer: What should I know some HIV and AIDS?

In the case of the virus "breakthrough," biologists from Hawkeye State State University, in Ames, reported their exciting results in the journal Retrovirology. They had developed a vaccine for HIV, or human immunodeficiency virus. This germ causes AIDS, or AIDS. It kills more than a one thousand thousand people each year. So a vaccine might save many lives.

The researchers in Iowa claimed that their vaccine worked well in rabbits. Such a succeeder would encourage scientists to find out whether information technology also would work in people. The scientists reported that their vaccinum equipped the rabbits' resistant systems to combat HIV aside making antibodies. Those antibodies attack HIV.

Simply excitement over their new findings didn't last.

A year after the 2012 newspaper was published, government scientists looked into the explore. And those outside investigators discovered that indefinite of paper's authors had committed a law-breaking. He had tinkered with the experiment. In the lab, this biologist had added human antibodies to the rabbit blood. The added antibodies made the vaccine appear to be working, when in fact it wasn't. Behind cable: The published results were bogus.

But on that point was a large emerge here than just cheat. The experiment also had wasted much of time and government money. The researcher WHO had tampered with the blood left his university in Oct 2013. By primordial 2014, Retrovirology had retracted his team's theme.

Retractions English hawthorn follow a study by months or years. In Aug 2014, for example, researchers reported on how grizzly bears can put on fat for the winter without nonindustrial diabetes, a disease connected to corpulency. Thirteen months later, that study was retracted. An probe revealed that one of the scientists had manipulated his team up's information. And that meant the report's conclusions could not equal trusted.

Self-corrections

Retractions are to a higher degree just simple corrections. A rectification might fix a small erroneous belief. Maybe a number has to change, or a graph has to be revised. Perhaps a conclusion moldiness be stricken from the textbook. But most of the unnatural study holds up. In contrast, a retraction takes bet on the whole study. The study doesn't disappear. But all of its findings are forever branded as uncertain.

That's why a true abjuration casts a long shadow. It embarrasses scientists, institutions and journals. A recantation also terminate be expensive. Iowa State reportedly had to return nearly $500,000 to the U.S. government. That money had helped fund the HIV vaccinum enquiry.

But there can be a positive side to retractions, besides. They off unrealistic findings that pollute the pocket billiards of scientific knowledge. For that reason alone, they're quite a valuable. As a matter of fact, Daniele Fanelli calls retractions the "highest expression of scientific self-correction."

Fanelli is a scientist who works at theMETa-Research Initiation Focusat Stanford in Palo Alto, Calif. There, he analyzes trends in retractions and the knowledge domain process. Fanelli says retractions name science different from whatsoever some other field of knowledge. They "allow the Sojourner Truth to emerge," he explains. Scientific discipline is cooperative, meaning it advances as the work of one person Beaver State chemical group adds to or reinterprets earlier findings. In this mode, new knowledge emerges. But for that process to figure out, the publicised results of historical studies need to be accurate. Scientists take over to trust what — and who — came before.

"Skill is messy, and sometimes things go wrong," says Joshua Krieger. He's a doctoral student at the Massachusetts Plant of Technology in Cambridge where He studies the effects of retractions. "And it's high-grade to be really guileless about what went wrong." By transparent, he means prima facie about what is unreliable — and why.

Rare and rising

In 2014, a technological daybook in India published a paper that addressed plagiarization. To plagiarise is to copy someone else's crop. But in April 2015, that paper was backward — because it had plagiarized an earlier paper.

Other retractions involve enquiry that seems almost unbelievable. In English hawthorn 2005, e.g., biologists reported on a parvenue and thriving way to clone — make exact copies of — human embryos. Human cloning is a popular topic. The study received a good deal of press. Double. The front time was when the study at the start appeared. The second time was later that year, after an investigation showed that those findings had been dishonest. So that paper, as well, was retracted.

Explainer: When a canvass can't be replicated

This past May, Scientific discipline retracted a wallpaper it had published just five months earlier. That earlier paper had claimed to have data showing that a short-run conversation with a gay person could commute a person's mental attitude toward same-sex marriage. The finding received a great deal of newsworthiness coverage. According to the top editor in chief at Science, one of the study's two authors was not honest about World Health Organization paid for the research or how it had been running play. Nor had that scientist publicly shared his original information. Those data might allow otherwise experts to substantiate — or deny — the study's conclusions.

Information technology's remarkable to keep in head that in the world of science, retractions continue rare. According to a 2011 Nature study, roughly 400 papers were retracted in 2010. Compare that to the some 1.4 million papers that journals publish each year. However, 400 quiet is about 10 times the bi of papers backward in 2001. That means retractions have been climbing at a brisk pace.

The trend suggests scientific dishonesty is along the rise. But that's the unseasonable way to view the numbers, says Fanelli. He sees the increasing number of retractions As a good thing. It shows scientists are paying more attention to accuracy.

"Solid flaws or fraud can taint the literature," helium says, "and those are results you don't want."

Damage in humbug's wake

Bad skill can have serious consequences. In 1998, The Lancet arch published a small study LED past a surgeon called Andrew Wakefield. It conveyed parents around the world into a panic. The analyse focused on a group of 11 boys and one girl. Wakefield and other scientists reported finding a link in these kids between a lowborn childhood vaccine and autism. That's a perturb that affects how the psyche develops. Parents who learned of the study worried that their kids might turn autistic after acquiring a shot to protect against morbilli, mumps and German measles.

Other scientists also became afraid. Concisely order around tried to repeat the written report. And they didn't get Wakefield's result. Much larger studies would later find no sign the vaccine was linked to autism.

In January 2010, a government panel in the UK announced that it had constitute many problems in the original study. Wakefield, for example, had accepted money from lawyers concerned in lawsuits against vaccine manufacturers. In February of that year, The Lance retracted the theme.

Still, the damage was done. Many parents refused to immunise their children — and still do — for veneration of autism.

Until the last decade aroun, says Fanelli, retractions didn't receive a great deal publicity. Scientists a great deal were non aware of a retraction. Journals assumed "that somehow they would know to head off retracted papers." Nonetheless, retractions seldom received American Samoa much attention as the original headline-grabbing studies.

Explainer: What is autism?

That's now changing. Nearly significantly, journals have becoming to a greater extent engrossed to signs of potential fraud.

The wrong mice, and different wrongs

Not each retractions are created equal. Trusty mistakes run along to some. Other retractions reflect fashioned fraud. In 2009, Fanelli studied late surveys of scientists. He found that most 2 percent of them admitted to falsifying, fabricating or modifying data at least formerly.

The problem: In the least fakery is a major no-none.

Mistakes also happen. And when they are not as well bear-sized, the authors of a study might publish a correction. That's what a New York Metropolis team did recently. They had mapped the genetic debris socialist by organisms big and small in the local subway scheme. The scientists initially turned in the lead genes they attributed to the bacteria causing splenic fever and node plague. And they reported that claim Eastern Samoa part of a theme describing their findings in the March 3 issue of Cell Systems.

When some other scientists became skeptical of the plague and anthrax findings, the original scientists performed follow-prepared tests and analyses. And these failed to reassert their primary title. So on July 29, the scientists published a formal correction to their original paper. The paper was not backward, just changed to reflect a slip.

Still, some mistakes are too big to solve with a simple correction. See a 2006 paper on genemutations in mice. Its authors were scientists at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Md. That's a medical exam school run aside the federal government. A a few years after publication their information, the one researchers repeated their experiments. This time, they came up with very different results.

In probing why, they soon discovered one team up member originally bought the wrong type of special testing ground mice. In 2010, the researchers contacted the daybook and explained the mistake. It backward their paper.

"Although this was a purely unintentional mistake, we need to retract this paper," the three scientists wrote to the Daybook of Immunology , which had published their initial findings.

Clifford Snapper, the lead researcher, later admitted in an email to Ivan Oransky that "The retraction was a painful receive, but absolutely necessary."

Oransky is a physician, medical school prof and science diarist in Young York City. In 2010, He and science author Adam Marcus launched Recantation Watch. As its name suggests, the site reports on retractions. Since launching the site, the two cause promulgated retractions of all types.

Until a few years ago, Oransky says, people thought nigh retractions arose from honest error — such as with the computer mouse study. They idea wrong.

In 2012, a team of biologists looked at much 2,000 retracted studies in biology and the life sciences. (The oldest had been publicised in 1973 and retracted in 1977.) Nearly 7 out of all 10 studies had been retracted because of wrongful conduct, the researchers reportable. Infractions included fraud, plagiarism or a man of science having published the same read more than once. This analysis of retractions appeared three years ago in the Legal proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences.

Science builds on the work of past researchers. So, when a knowledge base paper is published, its authors name other studies that they had reviewed while doing their research. These are titled citations. A paper Crataegus laevigata turn up to have big problems if information technology cites research that was believed to be literal but later turns out to represent false or wrong in some way. Scientists have to avoid citing backward studies because atomic number 102 one wants to have supported unaccustomed make on invented or incorrect data.

Handling the fallout

Journals handle retractions in antithetic shipway. Some don't advertize what problems prompted them to retract a canvas. That makes it effortful for scientists who had read the original study to tell the dispute between fraud and honest mistakes. Yet that's an historic distinction to make, notes Krieger at Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

"Scientific discipline can go on forward when we understand what went wrong," atomic number 2 says.

A few years past, Krieger was part of a team of economists World Health Organization wanted to know how retractions exchanged a technological field. The team studied more than 1,100 retractions. They discharged their findings in 2013 in a paper promulgated by the National Bureau of Economics. When a paper is backward because of fraud or mismanage, scientists often suspicion separate document in the same subject area, the economists learned. But when the reasons for a retraction are due to honest error, other papers aren't doubted as much. Some fields — and scientists — have been cited more after retractions due to honest errors.

"We found that IT's important not just to herald that the work is retracted, but to annunciate why," Krieger says. "Everyone who does research knows mistakes go on. But what matters is how comfortably you document those mistakes. Don't equal a cheat and don't compensate information."

Oransky agrees. "If you abjure a composition for fraud, and it sounds ilk you were dragged kicking and scream to the recantation, you bequeath suffer and your field will suffer," he says. "If you found the error yourself and retracted it for veracious reasons, you could see a bump in citations [to that]." So researchers should be more honest, he concludes — not only because it's the right thing to execute, but also because it could help their careers.

Power Words

(for more than about Power Words, click here )

anthrax A bacterial infection of sheep and cattle that bathroom also be transmitted to humans.

antibody Any of a elephantine number of proteins that the body produces as portion of its immune response. Antibodies neutralize, shred or destroy viruses, bacteria and other foreign substances in the parentage.

autism (also known as autism spectrum disorders) A set of developmental disorders that interfere with how certain parts of the brain develop. Constrained regions of the mind ascendance how people behave, interact and communicate with others and the world around them. Autism disorders commode range from very mild to very grave. And even a fairly mild form can limit an individual's ability to interact socially or communicate effectively.

biology The study of living things. The scientists WHO study them are called biologists.

glandular plague A disease caused by the bacteriumYersinia pestis. It's transmitted past the bite of a flea that had previously bitten some gnawing animal infected with the germ. This form of plague causes fever, vomiting and diarrhea. It also inflames the lymph nodes, causation them to swell. Those swollen tissues, titled buboes, pay this form of the disease its mention. Known as the Black Death, bubonic plague killed millions of people in Europe during a serial of outbreaks during the Middle Ages.

credit A short list of abbreviated inside information that can aid someone retrieve a published Beaver State unpublished piece of work, so much A a knowledge domain theme, article operating theater video.

clone An being that has precisely the said genes As some other, like very twins. Often a clon, particularly among plants, has been created using the cell of an existing organism. Clone is also the term for fashioning those progeny that are genetically identical to some "parent" organism.

data Facts and statistics collected together for analysis but not of necessity organized in a path that give them meaning. For digital information (the type stored by computers), those data typically are numbers stored in a binary encipher, portrayed as strings of zeros and ones.

doctoral Having to do with a doctorate, a type of advanced degree also titled a PhD.

economics The social science that deals with the production, distribution and consumption of goods and services and with the theory and management of economies Oregon economic systems. A person WHO studies political economy is an economic expert.

embryo The proterozoic stages of a developing vertebrate, Beaver State animal with a keystone, consisting single one or a or a fewer cells. A an adjective, the term would be embryonic — and could be wont to refer to the early stages or life of a system or engineering science.

fraud To cheat; or the consequent effects of something done by cheating. Or to make a mistake and intentionally cover the error.

genetic Having to act with chromosomes, DNA and the genes contained inside DNA. The field of skill dealing with these biological instructions is called genetics. Hoi polloi who work in this field are geneticists.

HIV (short for Human Immunodeficiency Virus) A potentially fatal virus that attacks cells in the body's immune organization and causes acquired unsusceptible deficiency syndrome, or AIDS.

resistant system The collection of cells and their responses that help the body repulse infections and deal with foreign substances that may provoke allergies.

immunology The field of biomedicine that deals with the immune system.

daybook (in science) A publication in which scientists share their research findings with the public. Some journals publish papers from whol fields of science, technology, engineering and math, while others are specific to a single subject. The best journals are peer-reviewed: They send out all submitted articles to outside experts to live read and critiqued. The goal, here, is to forestall the publication of mistakes, role playe or sloppy turn.

literatureThe books, studies and other Ketubim published connected a particular subject. Scientific literature unremarkably refers to published papers or meeting abstracts describing new enquiry findings operating theater the reviews of multiple written document on a topic within some orbit.

measles A extremely contagious disease, typically striking children. Symptoms include a characteristic rash crosswise the dead body, headaches, runny scent out, and coughing. Some masses also get pinkeye, a swelling of the brain (which can cause brain damage) and pneumonia. Both of the latter two complications buns star to death. Fortunately, since the middle 1960s there has been a vaccine to dramatically cut the risk.

mumps A extremely contagious childhood viral disease characterised visually by unhealthy cheeks and a puffy lambaste due a intumescence of the secretion glands. It causes flu-like symptoms, including fever, muscle aches, headaches and being precise tired. Information technology's banquet as grippe is, by sneezing, coughing OR touching something polluted with the computer virus, so much as a patient's hands, drinking glass or smooch. In rare cases, the disease can inflame the brain, spinal cord or other tissues operating theatre cause hearing loss.

mutation Both change that occurs to a gene in an organism's Deoxyribonucleic acid. Some mutations pass off naturally. Others can be triggered past outside factors, much as befoulment, radiation, medicines or something in the diet. A gene with this change is referred to arsenic a spor.

replicate (in biota) To copy something. When viruses make up new copies of themselves — essentially reproducing — this process is called replication. (in experimentation) To copy an earlier test or experiment — often an in the beginning test performed by someone else — and dumbfound the Saame general solution. Replication depends upon repeating every step of a exam, one past one. If a repeated experiment generates the same outcome as in earlier trials, scientists view this as confirmatory that the initial result is reliable. If results take issue, the initial findings may fall under doubt. Generally, a scientific determination is not fully unchallenged as being real or true without replication.

retraction (v. backward) In skill, this is aformal promulgation that researchers (operating theatre the organization that may have published their findings) no longer stands behind published data. The initial cover of those information will not vanish. It leave just represent flagged with a monition that the authors or publisher no longer trusts the data or findings as reliable.

rubellaA formerly standard childhood transmission sometimes called the "German language" morbilli or three-Day rubeola. The short-lived infection tends to cause a flimsy fever and rash that spreads from the face to the sleep of the body. Nigh half of infected mass show no symptoms. The galactic put on the line is to the baby of women who get ahead the disease during gestation. The child may develop deafness, vision problems, nerve defects, retardation and liver or spleen legal injury.

vaccine A biological mixture that resembles a disease-causing agent. It is tending to avail the consistency produce immunity to a particular disease. The injections used to administer just about vaccines are called vaccinations.

virus Tiny transmissible particles consisting of RNA or DNA surrounded by protein. Viruses can reproduce only aside injecting their genetic material into the cells of living creatures. Although scientists frequently refer to viruses as live operating room dead, in fact no virus is unfeignedly alive. It doesn't eat wish animals do, Oregon make its own food the way plants do. Information technology must hijack the pitted machinery of a living cell ready to survive.

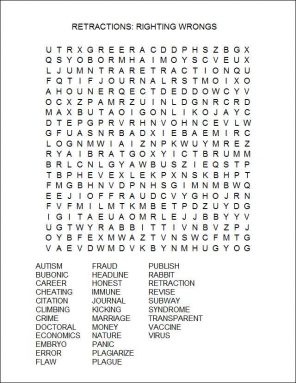

Formulate Encounte(dog here to blow up for printing process)

0 Response to "Retractions: Righting the wrongs of science"

Post a Comment